Author Susan Cain caught my attention with a quote in Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. In a passage on the extroverted nature of Evangelical Christianity, she quotes one priest’s advice to churches seeking a new pastor: he tells them to first check an applicant’s Myers-Briggs score. “‘If the first letter isn’t an “E” [for extrovert],’ he tells them, ‘think twice... I’m sure our Lord was [an extrovert].’” (Brackets and ellipsis in the original.)

Author Susan Cain caught my attention with a quote in Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. In a passage on the extroverted nature of Evangelical Christianity, she quotes one priest’s advice to churches seeking a new pastor: he tells them to first check an applicant’s Myers-Briggs score. “‘If the first letter isn’t an “E” [for extrovert],’ he tells them, ‘think twice... I’m sure our Lord was [an extrovert].’” (Brackets and ellipsis in the original.)I wonder if this priest means the Jesus who spent forty days alone in the desert; the Jesus whom Peter couldn’t find when the crowd clamored for His attention; the Jesus who repeatedly throughout the Gospel of Mark admonishes the apostles to keep His secrets; the Jesus who crossed the Sea of Galilee when the crowd got too noisy; the Jesus who, hours before His arrest, had the apostles wait outside the Garden of Gethsemane so He could pray alone.

Extraversion has become mandatory in most white American churches. From the public prayer and stem-winding sermons to the “passing of the peace” to the concluding coffee hour, parishioners are packed shoulder to shoulder, and not permitted a moment of quiet time alone with God. The near-constant stimulus of language, music, and human company makes church feel oppressive for those of us who would like a moment to talk honestly with God.

Even “silent prayer,” which in traditional monastic liturgy could occupy half the service, has been whittled in most churches to about thirty pre-scheduled seconds. Congregational prayers are primarily scripted. Times in the service when prior generations could expect an opportunity for private thoughts, like Communion, have become venues for one more hymn, soloist, or anthem. Programmed talk and music comprise nearly the whole liturgy.

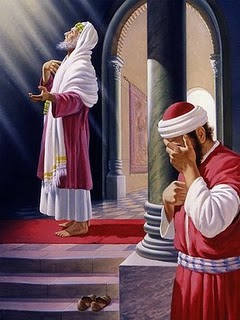

As Cain notes, many “seeker friendly” congregations no longer have pew Bibles. This means Christians cannot even grab a copy of the Good Book and read passages like that where Jesus warns believers not to pray on street corners like Pharisees, for “they have already received their reward.” Or the parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, where Jesus extols the soft-spoken prayer of a broken heart over the loud trumpeting of the self-righteous.

As Cain notes, many “seeker friendly” congregations no longer have pew Bibles. This means Christians cannot even grab a copy of the Good Book and read passages like that where Jesus warns believers not to pray on street corners like Pharisees, for “they have already received their reward.” Or the parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, where Jesus extols the soft-spoken prayer of a broken heart over the loud trumpeting of the self-righteous.Though I lack evidence to support this, I blame the culture of televangelism. As many churches see volunteerism and other involvement steadily decrease, most parishioners see their flesh-and-blood pastors only one hour a week. However, the ubiquity of Christian radio and television means that many people have some form of message streaming at them for hours every day. Unfortunately, now as in Marshall McLuhan’s day, the medium is the message.

Media critic Neil Postman observed a quarter century ago, in Amusing Ourselves to Death, that television had cheapened Christian discourse. Because Christian sermons now enter our homes through the same devices that deliver old Seinfeld reruns and bawdy country ballads, they occupy the same space in our psyches. And if the TV and radio Christians don’t entertain, we will find somebody else who will deliver.

Too many pastors, reared in that televangelistic culture, fall into the trap of trying to secure ratings. Because a live church service, mainly made possible by volunteers, can never have the spectacle value of million-dollar multimedia extravaganzas, congregations try to close the gap with the stimulation of dozens—nay, hundreds—of bodies in proximity. For people seeking that elusive “worship high,” this tactic probably works.

Yet this goes right to what I've said before about the first person singular emphasis in modern worship. As long as my need to have my senses stimulated trumps our need to pray, or God’s need for a place in our hearts, church will remain an unsatisfying place for those who seek meaningful spirituality. Not for nothing has church attendance diminished as Christianity has gotten noisier, and religions like Wicca or Buddhism, which reward solitude, have grown.

Yet this goes right to what I've said before about the first person singular emphasis in modern worship. As long as my need to have my senses stimulated trumps our need to pray, or God’s need for a place in our hearts, church will remain an unsatisfying place for those who seek meaningful spirituality. Not for nothing has church attendance diminished as Christianity has gotten noisier, and religions like Wicca or Buddhism, which reward solitude, have grown.Some people will say that Christianity is not a solitary pursuit, and they’re right. The church described in Acts is unmistakably communitarian; and many parachurch organizations have sprung up recently to emulate that community. But groups like Rutba House, Shane Claiborne’s Simple Way, and other modern monastic groups give members rooms where they can, as Christ said, close their doors and pray in secret.

As Christians, we are all in this together. But that “together” consists of individuals, not a mass. Until we reclaim our right and ability to be quiet, together, we will wander in search of the ministry most of us know in our hearts that we have lost.

No comments:

Post a Comment