|

| Lloyd Alexander |

The first four volumes each ended with the promise that the story would continue. The hope of more, that somehow this epic could unfold in any direction. So it came as a shock when the end came. Narnia ended, I felt, when the story had played itself out, but Prydain wasn’t done. Alexander even made that plain in his explanation that more took place after the final chapter. We just didn’t get to see it. The story was done, and all the possibilities closed down.

This was the first time I spotted a reality that eventually became the largest concept in my treasury of literary axioms: middles are the best part of any book. I will go to the mat with you on any book you name. Beginnings carry the need to explain character, situation, and conflict, while endings have the burden of putting a bow on all those concepts. Middles simply revel in untrammeled possibility. When we imagine books we love, we always recall the middle.

Since I’ve already mentioned fantasy, consider Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings. Though arguably the Twentieth Century’s most influential book, it lags in both the early and late chapters. Tolkein felt the need for such intricate introductions and explanations that the Council of Elrond runs nearly as long as some entire novels. And observe how filmmaker Peter Jackson elided Tolkein’s long, talky denouement. Only the middle doesn’t suffer from either scene-setting or resolution.

|

| Joseph Conrad |

Many classic writers understood this truth, and thus didn’t try to enforce pat endings. Shakespeare left so many doors open in Hamlet that uncounted authors have tried to write sequels. What happened to Horatio and Fortinbras after the final curtain? What happened to the state of Denmark after every claimant to the throne killed every other claimant? The very unsolved nature of these questions gives it power.

Unfortunately, most sequels have been undisputed stinkers. I blame the authors’ evident need to solve every debate definitively. Only Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which butters its bread with existential ambiguity and, if anything, asks even more questions, merits our time. Nor is this problem unique to Shakespeare; consider all the authors who write sequels to the Odyssey or Pride and Prejudice—and how few are actually are worth reading.

Shakespeare, Homer, and Austen knew that, if they left important plot threads open, we would write our own stories. Even if we don’t literally put pen to paper, we tell stories to ourselves. We ask questions, we speculate on possibilities, and we put ourselves into the shoes of our favorite protagonists. We make meaning not from the completion of every concept the authors put on the page, but in the ability to join the story, which we can only do if the story remains open.

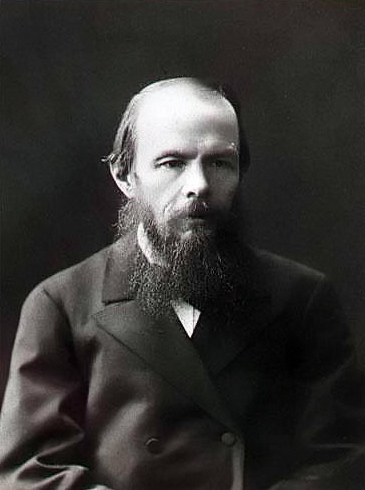

|

| Fyodor Dostoevsky |

Perhaps that’s why ongoing series novels dominate the current publishing domain. Maybe audiences like middles so much that they want stories to hang on. Though one particular conflict may resolve, our characters’ arcs remain intact, and continue to live in a world where anything can happen. Because we want to believe anything can happen in our world, as Lloyd Alexander taught me to hope so many years ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment