|

| President Obama's duet with Jimmy Fallon drew praise and blame from entirely predictable circles. |

Unaddressed amid this artificial controversy lingers the real question: what is the role of the American President in today’s world? Should the person elected to that office hold himself (or herself) aloof from the glitz of entertainment? Or is the President a celebrity on a par with rock stars and actors? The answer, if we look at who voters have favored all the way back to the Founders’ time, seems plain: the President, for good or ill, is very much a pop culture figure.

When Nixon appeared on Laugh-In, he was considered an accidental candidate, likely to win only because his opponent, Hubert Humphrey, couldn’t wash off the stink of Lyndon Johnson. Voters in that newly technicolor world remembered Nixon’s televised 1960 debate with John Kennedy, when Nixon’s disdain for stage makeup made him resemble a pile of old socks. Appearing on Laugh-In let America see he was in on the joke—that he was their President.

Nixon had the aid, that year, of former Mike Douglas producer Roger Ailes. Later, Ailes would produce Rush Limbaugh’s ill-considered TV program, before shepherding Fox News into existence. Ailes brought his TV experience to bear on his political goals, and helped bring politics into the television age. If one man holds the bag for weird on-camera behavior by candidates and office-holders, that man is Roger Ailes.

|

| Candidate Nixon made his age, unhipness, and confusion the very heart of the joke. |

Admirers called Reagan the Great Communicator, but reread his most celebrated speeches. He produced stirring quotes in abundance (“Well, there you go again;” “Tear down this wall!”), yet few policy statements. And Americans rewarded him for that. Compared to the notoriously inarticulate Jimmy Carter, or the stultifying Walter Mondale, Reagan won votes by giving tired, overloaded voters something exciting and unambiguous to hang onto.

The techniques Reagan pioneered found their ne plus ultra in George W. Bush. Twice Bush ran against knowledgeable but dull opponents, and won, as much as anything, on the fact that he looked like a real human beside starched shirts like Gore and Kerry. Even his supporters admitted Bush ran vague campaigns (though he seemed a model of specificity compared to Barack Obama), but he played the right emotional keys to keep voters’ eyes and ears on him.

Few Presidents have courted the media so blatantly as to appear on a midnight comedy talk show (though John Kerry, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Bill and Hillary Clinton [separately] talked politics with Jay Leno). But over a dozen Presidents from both parties have attended the annual White House Correspondents’ Dinner. Many have tried stand-up comedy. And why shouldn’t they? Candidates and office-holders perform for journalists regularly.

|

| Comedy has always weighed in on politics; turnabout is fair play. |

Even Thomas Jefferson, often painted as stiff and doctrinaire, could work a crowd. His decision to ride his own horse in his inaugural parade, with neither a hat nor a powdered wig, made a deliberate statement as to who he believed he had been elected to serve. This marked a turning point in American history, when pretense became a political liability. But it was also a high-water mark in deliberate messaging.

President Obama simply continued the tradition of using the tools of his time to carry the message where it needs to go. How many people who would tune out another Presidential speech paid attention because of the format and venue? Sure, slow jamming the news lacks the faux gravitas of Disney’s Hall of Presidents. But it carries the mark of communications genius, and refined cultural savvy.

It got to where I couldn’t decide who I wanted to slap more, Sean or his various interlocutors. On the one hand, Sean’s frustrating passivity made me want to grab his lapels and shout at him to grow a pair. On the other hand, everyone around him wants to burden Sean knows something about him, to the point where it strains credibility. Dick Nixon wanted to hang Uncle Mike out to dry, and Sean never heard that story? From anybody? Ever? Please.

It got to where I couldn’t decide who I wanted to slap more, Sean or his various interlocutors. On the one hand, Sean’s frustrating passivity made me want to grab his lapels and shout at him to grow a pair. On the other hand, everyone around him wants to burden Sean knows something about him, to the point where it strains credibility. Dick Nixon wanted to hang Uncle Mike out to dry, and Sean never heard that story? From anybody? Ever? Please.

Some of Angler’s themes will not surprise anyone who reads Christian fiction. He distrusts earthly authorities, especially centralized government, which entangles citizens in others’ vision. Governments may grant stability, but what the state gives, the state takes away. And he sees the loss of tradition as a diminution of human potential. Logan Langly rebels against a culture that exists entirely to feed short-term wants.

Some of Angler’s themes will not surprise anyone who reads Christian fiction. He distrusts earthly authorities, especially centralized government, which entangles citizens in others’ vision. Governments may grant stability, but what the state gives, the state takes away. And he sees the loss of tradition as a diminution of human potential. Logan Langly rebels against a culture that exists entirely to feed short-term wants. Let’s pause to see the world from that perspective. Sarah Palin has claimed, following her doomed national campaign, that her humble roots and relative lack of sophistication make her uniquely qualified to represent Americans in Washington. Urban magazines like the New Yorker easily deride that attitude, since it implies any schlub off the farm could be President. Yet I think Palin means nothing of the sort.

Let’s pause to see the world from that perspective. Sarah Palin has claimed, following her doomed national campaign, that her humble roots and relative lack of sophistication make her uniquely qualified to represent Americans in Washington. Urban magazines like the New Yorker easily deride that attitude, since it implies any schlub off the farm could be President. Yet I think Palin means nothing of the sort. Let’s follow the logic:

Let’s follow the logic:

Once we know how we reached this position, Hunter examines how we can emerge to a life of freedom and productivity. He contrasts “modern and futile” solutions, which in his telling are mere rationalizations, to the “ancient and fruitful” traditions which have stood the test of time. His solutions come from Christianity (and in a few cases, though he doesn’t acknowledge it, even earlier), yet they speak to the disorder at the heart of our modern struggle.

Once we know how we reached this position, Hunter examines how we can emerge to a life of freedom and productivity. He contrasts “modern and futile” solutions, which in his telling are mere rationalizations, to the “ancient and fruitful” traditions which have stood the test of time. His solutions come from Christianity (and in a few cases, though he doesn’t acknowledge it, even earlier), yet they speak to the disorder at the heart of our modern struggle. Author Susan Cain caught my attention with a quote in

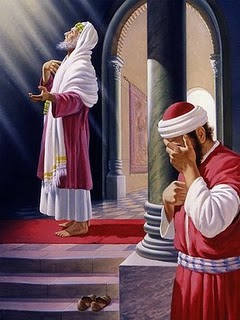

Author Susan Cain caught my attention with a quote in  As Cain notes, many “seeker friendly” congregations no longer have pew Bibles. This means Christians cannot even grab a copy of the Good Book and read passages like that where Jesus warns believers not to pray on street corners like Pharisees, for “they have already received their reward.” Or the parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, where Jesus extols the soft-spoken prayer of a broken heart over the loud trumpeting of the self-righteous.

As Cain notes, many “seeker friendly” congregations no longer have pew Bibles. This means Christians cannot even grab a copy of the Good Book and read passages like that where Jesus warns believers not to pray on street corners like Pharisees, for “they have already received their reward.” Or the parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector, where Jesus extols the soft-spoken prayer of a broken heart over the loud trumpeting of the self-righteous. Yet this goes right to

Yet this goes right to  In “Serenity,” the pilot episode for Joss Whedon’s Firefly, Shepherd Book looks like the show’s biggest misfire. Though he leaves his abbey to seek the world, this monk seems unprepared for the conflict, moral compromise, and violence he encounters. In his final scene, he confesses to another character: “I think I’m on the wrong ship.” Anyone who has spent time around most pastors (“pastor” translates to English as “shepherd”) would roll their eyes.

In “Serenity,” the pilot episode for Joss Whedon’s Firefly, Shepherd Book looks like the show’s biggest misfire. Though he leaves his abbey to seek the world, this monk seems unprepared for the conflict, moral compromise, and violence he encounters. In his final scene, he confesses to another character: “I think I’m on the wrong ship.” Anyone who has spent time around most pastors (“pastor” translates to English as “shepherd”) would roll their eyes.

Yet he is no mere actor, nor is his Christianity a veneer. In times of stress or fear for his life, he reaches first for his Bible. He is able to quote Scripture and conventional forms of theology, and when River Tam tries to critique the Bible from a scientific perspective, he provides a strong defense of why we should not read Scripture literally. In short, despite his violence, he also makes a good poster boy for modern Christian humanism.

Yet he is no mere actor, nor is his Christianity a veneer. In times of stress or fear for his life, he reaches first for his Bible. He is able to quote Scripture and conventional forms of theology, and when River Tam tries to critique the Bible from a scientific perspective, he provides a strong defense of why we should not read Scripture literally. In short, despite his violence, he also makes a good poster boy for modern Christian humanism.