|

| A boater chews up the water near the top of this photo |

Sarah and I sat on the docks, watching the waves on the Lake of the Ozarks and listening to birdsong from the forested shore. The floating dock bobbed gently with the waters of Missouri’s largest tourist attraction. With over eleven hundred miles of shoreline, most of it privately owned, Lake of the Ozarks attracts vacationers from the American midlands who want to relax on the water without the time and expense of flying to the coasts.

Then some nincompoop in a pontoon boat shot by at absurd speeds, creating a wake that sent our floating dock reeling. As Sarah gripped her seat with both hands, waiting for the turbulence to subside, she rolled her eyes over at me. “It’s like some people want to be on the water,” she said, in tones of long-suffering patience, “and others want to dominate the water.”

Something in Sarah’s comment struck me as both apropos, and ironically jarring. Lake of the Ozarks is a man-made reservoir, created when the Bagnell Dam stopped the Osage River back in 1931. It exists because the Union Electric Company sought to dominate the water. From our position, perched between lush forested shore and the flat, picturesque water, it’s easy to mistake the lake for “nature,” but its very existence represents human industry and artificiality.

Yet simultaneously, we’re witnessing different reactions. Sarah and I struggle to attune ourselves to the forests, the water, to “nature.” Sure, the lake is artificial, but nature has adapted itself to humankind’s influences, and now we’re adapting ourselves to nature. We bring only our clothes to the shoreline, dangle our feet in the water, and attempt to exist entirely as we are, in this place and moment, without making demands.

Meanwhile, others bring industrial modernity onto the water. Speedboats, water skiers, pontoon boats, and floating party platforms crisscross the water throughout the daylight hours. Most have noisy gas-burning outboard motors; many blast loud rock or country music from elaborate onboard speaker systems. Their passengers want the dopamine hit deriving from bright sunlight, loud sounds, and fast speeds. They consider “nature” a negative space onto which they draw their experiences.

Traditional religions require humans to adjust their mental rhythms away from worldly tempos. Sung hymns, chants, and unison prayers force congregants to slow their mental wavelengths, while silent prayers and mindfulness meditations require congregants to practice sitting still and listening. Traditional religions believe that God, the spirits, or Truth exists at a tempo different from commerce, industry, and work.

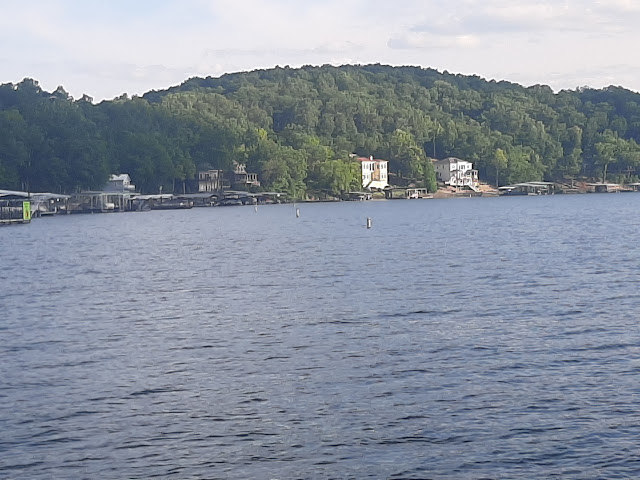

|

| Private vacation homes along the shores of the Lake of the Ozarks |

Capitalism, by contrast, forces people to accelerate their internal rhythms. Assembly lines, retail outlets, and high-value finance require us to think, speak, and act quickly. This acceleration spills into non-working life. Consider drivers who get onto rural highways and attempt to achieve speeds only possible on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Lake of the Ozarks, at over ninety miles long, lets boaters reach and maintain speeds usually reserved for the open ocean.

This constant, almost Sonic the Hedgehog-like demand that we “Gotta Go Fast” has deleterious consequences. Capitalist America has the world’s highest rates of clinical depression, stress ulcers, and Type-II diabetes. While slowing down wouldn’t magically remove these facts, the tendency to carry our demand for machine-like speed into our off hours and vacations reflects the ways capitalism changes our brains, even when we’re not working.

Meditating in forests and lakes, while pleasant, isn’t necessary to find our inner rhythms. Cities have rhythms, reflected in the ways people walk the streets, and how they stop to converse or shop. London’s or Boston’s notorious winding pedestrian byways bespeak this inner rhythm. Capitalists naturally colonize our cities by sequestering us in hermetically sealed cars, and razing pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves in the name of “urban renewal.”

Watching speedboaters crisscross the lake at absurd speeds, I can’t help wondering whether their “vacations” will return them to workaday life any better prepared for capitalism’s punishing paces. Instead of resting, recovering themselves, and finding their inner rhythms, they’ve dragged modernity’s breakneck industrial pace onto the water. No wonder they’re blasting classic rock from their speakers: despite their numbers, I suspect they’re lonely.

As the boaters’ wake subsided, Sarah and I returned to the rhythm of the water. The smell of rich organic loam filled our noses and permeated our clothes. Birds that had paused in their singing returned, and a cool northeast wind rustled the leaves. “Nature” doesn’t exist, as I’ve written before, but nature always reestablishes balance after humans quit disturbing it. All humans have to do is listen.

No comments:

Post a Comment