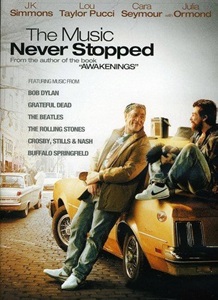

Jim Kohlberg (director), The Music Never Stopped (2011)

This film is based on an article by Oliver Sacks, whose writings also inspired the 1990 tear-jerker Awakenings. Like that film, this one hides an essentially optimistic tale of human redemption behind a superficially maudlin, slow-moving veneer. There’s a fine line between “affecting” and “manipulative” in filmmaking, and which side of that line you see this movie on, depends on what you bring to the experience.

This film is based on an article by Oliver Sacks, whose writings also inspired the 1990 tear-jerker Awakenings. Like that film, this one hides an essentially optimistic tale of human redemption behind a superficially maudlin, slow-moving veneer. There’s a fine line between “affecting” and “manipulative” in filmmaking, and which side of that line you see this movie on, depends on what you bring to the experience.JK Simmons (“Law & Order,” “Spider-Man”) plays Henry Sawyer, a burned out engineer whose life apparently stopped in the Eisenhower years. His estranged ex-hippie son Gabriel (relative unknown Lou Taylor Pucci) reappears after twenty years, but a brain tumor has erased all memories formed after 1970. Music therapist Dianne Daley (Julia Ormond) reawakens Gabriel’s higher functions using classic rock on vinyl, particularly the Grateful Dead, much to Gabriel’s reactionary father’s chagrin.

Simmons almost never plays lead roles, and it’s unusual for actors of his age to carry feature-length films, so we’re moving outside Hollywood’s comfort zone on two levels. Kudos for that. As Sawyer, Simmons plays a man who has stopped keeping up with society. His household decor is antiquated, even for the 1986 setting, and he refuses to learn computer-assisted drafting and other trade tools. Sawyer simply rejects all modernity.

Gabriel is supposedly around 35, but looks 18 under layers of beard. He thinks it’s only two years since he fled his father’s constricting suburban world for Greenwich Village bohemianism. Because his tumor also destroyed his inhibitions, his classic rock also lets him tell his father all the secrets he previously bottled up, but because he creates only fleeting, isolated new memories, he never gains closure, persistently revisiting old pains.

Because Gabriel cannot change or grow, Henry must adapt to Gabriel’s illness. A jazz purist, Henry must learn to appreciate classic rock, rebuilding himself as America’s oldest Deadhead. Even as his own health slowly fails, he becomes broadly hip, awakening himself to new experiences and previously untapped reserves of enthusiasm. Henry, in second youth, and Gabriel, trapped in permanent adolescence, finally make the connection they couldn’t in 1966.

|

| JK Simmons (left) and Lou Taylor Pucci |

We could continue. The film situates the Sawyers, including hospitalized Gabriel, in the same suburban, preponderantly white, bourgeois environment Gabriel so ostentatiously fled. Except for one pretty Hispanic orderly, nobody confronts poor or non-white characters. And note, the only significant character of color is explicitly romanticized. Why doesn’t hippie Gabriel rebel afresh? Perhaps because, beneath its egalitarian baggage, hippie bohemianism was an innately white middle-class conceit anyway.

This film’s small-budget, art house texture eschews glamor and spectacle, but this opens other possibilities. Because director Jim Kohlberg maintains his understated tone without bogging down, he permits opportunities for quiet humor and character development. It’s so quiet, in fact, that Hollywood-raised film children may get lost. Henry’s tear-filled climactic monologue will probably strike film audiences as sentimental, but book readers will appreciate its relative restraint and lack of bombast.

Kohlberg probably spent more on soundtrack rights than his thrift-shop set design, lending the film a shopworn look but a rich, surprisingly nuanced soundscape. For instance, Peggy Lee’s version of “Till There Was You” looms large in the movie’s themes; but in one key scene, stodgy Henry replaces it with the Beatles’ rendition. This willingness to leap forward seven years is remarkable for the character, without requiring aggressive directorial jazz hands.

Browsing professional reviews, I’ve seen two basic threads: critics who hate this film because it doesn’t resemble typical Hollywood fare, and critics who embrace it for the same reason. Mass media insidership makes a difference. Audiences accustomed to, and comfortable with, Hollywood culture will find this movie contrived and lethargic. Audiences who haven’t internalized the lingo will enjoy the relaxed pace and subtle, cerebral themes.

Fundamentally, this film is about the romanticized past. Set in 1986, it pits Henry, trapped in 1950, against Gabriel, trapped in 1968. But in era-hopping, it reminds us, the past isn’t frozen. As Dr. Daley notes, we constantly rewrite history in light of our present circumstances. What past, this film asks, would we agree to lock ourselves into? And when would we set ourselves free?

No comments:

Post a Comment