Christians once had an adversarial relationship with the state: many Roman believers went to martyrdom for refusing to recognize the Emperor as God made manifest. As Europe became Christian, however, the church enjoyed power and privilege, built on the belief that all citizens were parishioners, and vice versa. Now the church finds itself in a third arrangement: no longer persecuted, but no longer the peak of earthly power, either.

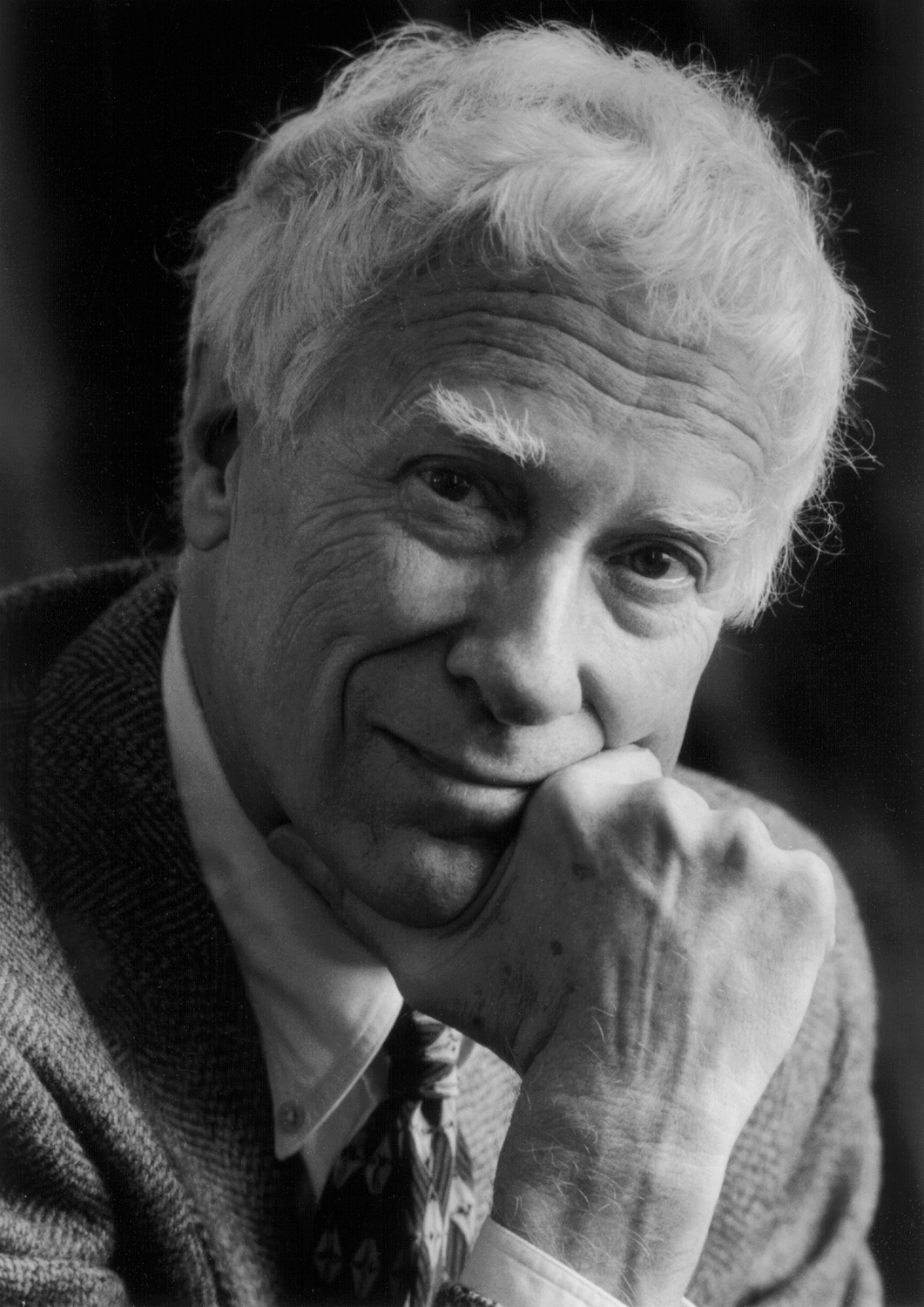

Christians once had an adversarial relationship with the state: many Roman believers went to martyrdom for refusing to recognize the Emperor as God made manifest. As Europe became Christian, however, the church enjoyed power and privilege, built on the belief that all citizens were parishioners, and vice versa. Now the church finds itself in a third arrangement: no longer persecuted, but no longer the peak of earthly power, either.Yale philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff endeavors, in his newest scholarly book, to address how Christians can frame this third arrangement for life in modern liberal democracy. Instead of longing for the past or fleeing the dilemma, as too many have tried, Wolterstorff proposes embracing the difficulty. Only then, he implies, will we have a meaningful relationship, not only with our God, but also with our state.

As Wolterstorff emphasizes around the middle of this short but remarkably rich book, “political theology” is a species of political science, not theology. That is, rather than dealing with the nature and desires of God, it addresses how people of theological insight should approach the institutions of power in this world. How should the church, and members thereof, conduct themselves toward the state? The answer defies easy summary.

Christians have traditionally struggled with our relationship to the state. In political discussions, some wag inevitably cites Romans 13:1-7. But if we must submit to the state, what of those Christians whom the Empire ordered to renounce Christ? Wolterstorff bookends this essay with the story of Polycarp, who as both a Roman citizen and Christian bishop, died when he could not appease this duality. Remember what Christ says about the servant of two masters.

Many recent theologians have tried to answer this same conundrum by asserting that Christians are under only God’s authority, or that earthly polity cannot extend to Christians or the church. Wolterstorff demonstrates how such views don’t withstand scrutiny. All Christians have the duality of earthly citizen and transcendent disciple, and if we try to smooth over that duality, we blunt the richness of life that both identities provide.

Wolterstorff reconciles the problem by reframing Romans 13. He believes most interpretations, since at least the Renaissance, have treated as central what he demonstrates to be a subsidiary argument. Wolterstorff believes Romans 13 actually specifies the state’s domain, and in so doing, circumscribes its authority. When the state exceeds its authority, as in enforcing racist laws, it has abandoned Romans 13, and Christians are right to resist such false power.

Wolterstorff reconciles the problem by reframing Romans 13. He believes most interpretations, since at least the Renaissance, have treated as central what he demonstrates to be a subsidiary argument. Wolterstorff believes Romans 13 actually specifies the state’s domain, and in so doing, circumscribes its authority. When the state exceeds its authority, as in enforcing racist laws, it has abandoned Romans 13, and Christians are right to resist such false power.Instead, Wolterstorff proposes a dual interpretation, in which state and church exist in tandem, each placing certain limits on the other. The state cannot, for instance, say who may attend worship, or even require any worship whatsoever. The church is free to practice what it believes right. By its very existence as a separate community within the polity, the church places limits on state authority.

But the state also imposes limits on the church. Christians cannot baptize anyone by force, as they once tried, or impress piety on secular laws. Individual believers may hold earthly power, but the church itself must stay out of power. When the church and state become entwined, each loses its distinct authority: the state has religious justifications for injustice, and the church loses sight of its divinely ordained mission in the vain pursuit of earthly power.

That’s not to say that church and state don’t have coinciding domains. Recent religious jeremiads on poverty and war come to mind. Consider a Venn diagram: two circles may overlap while retaining their unique identities. But when they become so enmeshed that we cannot tell where one ends and the other begins, or one swallows the other, we have a new breed, and one or (probably) both circles lose their distinct nature.

This book epitomizes the bromide “this book isn’t for everyone.” Wolterstorff’s approach, reliant on compressed language, intricate Aristotelian terminology, and numerous footnotes, requires a committed reader willing to take time. The author makes many points through allusion: having written on this topic for decades, Wolterstorff refuses to repeat himself, directing our attention to his prior publications. This book is for scholars and specialists, reflected in its steep price.

Rereading what I’ve written, I fear I’ve made Wolterstorff seem less complex than he is. Not so: he abhors the intellectual passivity with which some prominent theologians have tried to paper over modern polity. This book, though slim, is very, very hard. But it also more than justifies the effort in its ultimate liberating rewards.

No comments:

Post a Comment