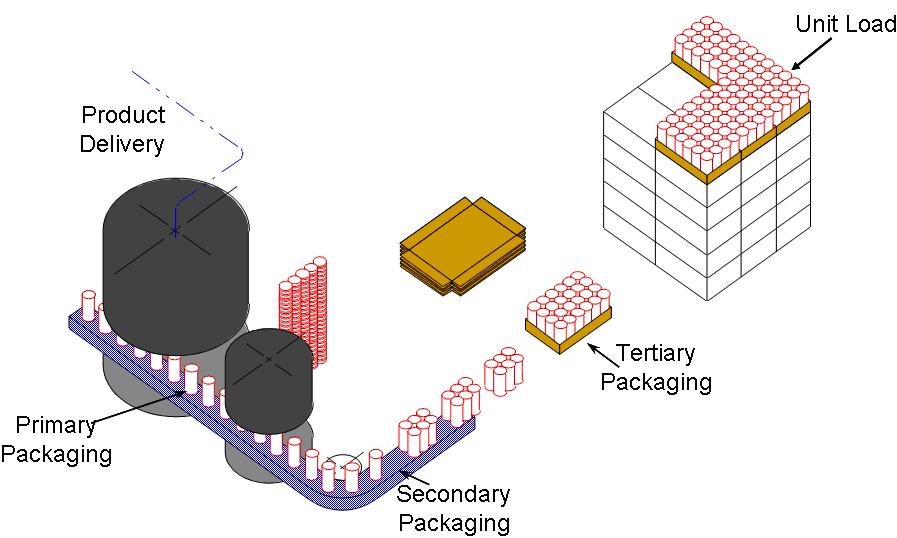

The other day at work, five of us worked the package line, putting completed units into sales cartons. Two people made (that is, folded) cartons; one person placed units in cartons; one person—me—placed rubber gaskets in cartons; and one person closed cartons to send them onto the case packer robot. One conveyor belt brought raw units in, and another conveyor carried packed units away.

The other day at work, five of us worked the package line, putting completed units into sales cartons. Two people made (that is, folded) cartons; one person placed units in cartons; one person—me—placed rubber gaskets in cartons; and one person closed cartons to send them onto the case packer robot. One conveyor belt brought raw units in, and another conveyor carried packed units away.I had the second easiest job that night, flipping a small rubber ring into a large target. I could daydream without hindering my job performance. But the conveyor moved fast enough that the closer inevitably fell behind and struggled to keep up. If she fell too far behind, she had to stop the conveyor until she caught up. But if she stopped the outgoing line, the incoming line kept bringing units, which formed a huge knot at the choke point.

Clearly my short-term interests were best served by letting the closer fight her own battles. I could shoegaze if I wanted, and what everyone else deemed a strenuous pace was, to me, pretty easy-going. But if she stopped the outgoing conveyor, we all had to deal with that huge knot. If I closed every fifth box, sacrificing my short-term interests, the closer could keep up, the knot would never form, and everyone was better served.

America’s political economy today is dominated by an attitude of “what’s mine is mine, and hands off.” Our tax laws and spending priorities reflect this attitude, as well as our charitable giving habits—while Americans donate more money than any other country in absolute terms, we have one of the lowest donation rates in the industrialized world. And we justify this in public discourse by appeals to capitalism and the free market.

But we forget that Adam Smith, author of capitalism’s foundational text, The Wealth of Nations, was no free market absolutist. He wrote that the wealthy had a moral obligation to pay greater revenues into the maintenance of society, making him an early proponent of the “Buffett Rule.” And he believed corporations, which manipulated massive volumes of what he termed “other people’s money,” were inherently untrustworthy.

But we forget that Adam Smith, author of capitalism’s foundational text, The Wealth of Nations, was no free market absolutist. He wrote that the wealthy had a moral obligation to pay greater revenues into the maintenance of society, making him an early proponent of the “Buffett Rule.” And he believed corporations, which manipulated massive volumes of what he termed “other people’s money,” were inherently untrustworthy.There is simply no empirical reason to believe an absolute free market helps anybody. Indeed, by letting the rich hoard wealth while the poor pound sand, we create an aristocratic class and “everybody else.” But anthropology proves that poverty incubates crime, so a permanent poor underclass is a breeding ground for lawlessness. Thus the wealthy spend more money guarding their hoarded wealth, and enjoy less of it.

Lacking an empirical basis, defenders of self-interest manufacture moral arguments. They term taxes “theft,” insist they don’t want their hard-earned money given to “welfare queens,” and decry “socialistic” intervention. Unfortunately, most world value systems, including the Christianity which social conservatives claim, reject accumulated wealth without concomitant responsibility to serve those less fortunate.

If I focus on my short-term self-interest, and count myself blessed here and now, without planning for the future, I set myself up for catastrophe in the long term. Whether by befouling the atmosphere, or producing a customer base that can’t afford my merchandise, or by permitting raw units to accumulate in the choke point, pursuing immediate interests will exact a price I have to pay in the future.

Taking time to close every fifth carton is not easy. I have to break my rhythm with a simple task to perform one that is slower and requires fine motor skills. Essentially, I need to shift between two very different muscle actions, which is a nuisance. But it’s a smaller nuisance than having to keep up with the sudden influx from the choke point. And it’s an act I perform alone, which benefits everybody on the line equally.

Sure, something else could set me back. A carton maker could fold one improperly, get caught trying to straighten it, and send ripples down the line. Or the product placer might knock one carton over, sending others tumbling like dominoes. But that could happen. If I don’t extend myself to help the closer, the knot at the choke point will happen. I consider the risk worth the cost.

Sure, something else could set me back. A carton maker could fold one improperly, get caught trying to straighten it, and send ripples down the line. Or the product placer might knock one carton over, sending others tumbling like dominoes. But that could happen. If I don’t extend myself to help the closer, the knot at the choke point will happen. I consider the risk worth the cost.I don’t advocate a Soviet-style collectivization of risk. History proves that this fails. But if we all give a little of our short-term interest into a pool of public generosity, the long-term rewards, individually and as a society, should more than pay for that investment. And we could all use a little long-term security in this dangerous world.

No comments:

Post a Comment