|

| Edward Murrow (left) and William Shirer pioneered journalistic techniques that remain standard today |

Steve Wick’s The Long Night: William L. Shirer and the Rise and Fall of the Third Reich appears as more than a memoir of a person. It reads like an indictment of current journalism: why do today’s news gatherers lack Shirer’s courage? While the presidential press corps eats anything appointed spokespeople spoon up, and business writers unquestioningly repeat corporate news releases, audiences long for difficult stories gathered deep in the trenches.

Fired from a prestigious European correspondent job deep in the Depression, Shirer was days away from losing everything when Edward Murrow hand-picked him to start CBS Radio’s second European bureau. His appointment coincided with Germany’s stirring aggression, and as a journalist in a police state, Shirer accepted a very difficult job: telling the truth in a nation where truth came from the state, not from reality.

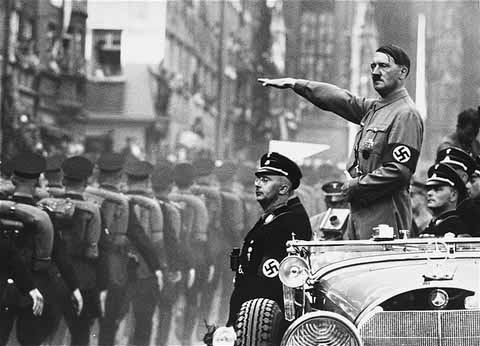

Fired from a prestigious European correspondent job deep in the Depression, Shirer was days away from losing everything when Edward Murrow hand-picked him to start CBS Radio’s second European bureau. His appointment coincided with Germany’s stirring aggression, and as a journalist in a police state, Shirer accepted a very difficult job: telling the truth in a nation where truth came from the state, not from reality.Faced with the choice of repeating inane propaganda, as many of his colleagues did, or being ejected from Germany, Shirer undertook an elaborate tapdance. His journalistic loyalties lay with the truth, not with expediency, and he risked his safety (and his Austrian wife’s life) to ensure the world saw the real Germany. But the state did everything in its power to bring Shirer to heel.

Reading this harrowing story, I remember complaints from embedded American reporters at least as early as Operation Desert Storm. By keeping journalists close by, and beholden to the military for even basic supplies and information, officers and the state they represented could control what facts the people knew. Reporters conducted intricate subterfuge to smuggle information out of the war zone.

Writers like Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber described President Bush’s press corps as possibly the most cowed ever. Reporters who deviated from the administration’s official line reported that they often found themselves locked out of important scoops. Despite promises of increased transparency, President Obama has treated journalists little better. Recall how dismally he handled the Wikileaks affair.

|

| Shirer remained unable to forgive the German people well into his eighties |

People in power never want the full truth told. History proves this time and again, although journalists who want official commendation court politicians, generals, and capitalists. Yet how many journalists enjoying insider status make significant breakthroughs? Shirer sat across the table from Goebbels and Ribbentrop, both of whom offered access if he would only report their propaganda unquestioningly. Shirer had the integrity to refuse.

American newspapers founder under the weight of their credentialed, university-taught writers’ stables, complaining that TV and the Internet have dealt their deathblow. Audiences roll their eyes, knowing that journalistic timidity, not technology, has rendered our news toothless and bland. What journalist today would say, with Ambrose Bierce: “We know what happens to people who stay in the middle of the road. They get run over”?

Shirer’s experiences in Berlin, and his journalistic acumen, helped him craft his classic, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. While scholars flinched from addressing the greatest event of their generation, Shirer culled thousands of documents, and his own diaries, to recreate for Americans the social circumstances that permitted the Nazi atrocity. His book remains the definitive call to stand fast against extremism and obdurancy.

Shirer’s experiences in Berlin, and his journalistic acumen, helped him craft his classic, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. While scholars flinched from addressing the greatest event of their generation, Shirer culled thousands of documents, and his own diaries, to recreate for Americans the social circumstances that permitted the Nazi atrocity. His book remains the definitive call to stand fast against extremism and obdurancy.It would be a mistake to compare today’s situation to Germany in 1932. Yet consider how many matching traits apply: economic uncertainty, belief in a unitary executive, and a populace that prefers security to liberty. When Steve Wick describes the inflammatory rhetoric and violence Shirer observed in Depression-era Paris, it’s hard not to draw parallels to the political sharpshooting that enforces such a sharp division between Right and Left today.

History is an ever-patient teacher, yet her pupils remain recalcitrant. One could hope that the lessons Shirer learned in his generation could penetrate the popular mind today. Cynicism is a cheap excuse not to get involved, yet it has become hard to remain optimistic.

No comments:

Post a Comment