But Campbell complained that we retain the same myths the ancients used to face their world. Ancestral religions and philosophies don’t address modern needs—and, Campbell charged, nothing endures long enough to attain mythic status anymore. Two Nebraska critics, David Whitt and John Perlich, disagree. In Sith, Slayers, Stargates, + Cyborgs, and its follow-up, Millennial Mythmaking, attest that science fiction and fantasy fill that gap.

Fellow Browncoats, ask yourselves: Why do we continue watching Firefly, years after the show ended without completing one season? Do we, as a society, struggle to maintain “independence” against a monolithic “Alliance” that dominates and marginalizes us? As meaningful jobs give way to make-work and we struggle to find our way without a map, maybe we do. We find ourselves alienated from our lives, struggling to comprehend a world changing without us.

Fellow Browncoats, ask yourselves: Why do we continue watching Firefly, years after the show ended without completing one season? Do we, as a society, struggle to maintain “independence” against a monolithic “Alliance” that dominates and marginalizes us? As meaningful jobs give way to make-work and we struggle to find our way without a map, maybe we do. We find ourselves alienated from our lives, struggling to comprehend a world changing without us.Firefly appropriates the frontier mythology fundamental to science fiction, where “new life” awaits beyond the next star. But notice that the ensemble never has a chance to settle. This is no pioneer frontier; the Serenity crew has become guests in their own lives. Despite references to “border moons” and urbane “core worlds,” there’s no sense that anyone will ever call the dusty horizon home. Tumbleweed restlessness is not a transition here; it’s intractable reality.

Sci-fi and fantasy, more than any other genre, reflect the culture in which they originate. That’s why they seldom translate across time. Anyone who remembers the 1968 Planet of the Apes must recognize the cultural issues it brings to the surface. Though its anti-war message has become axiomatic, the racial concerns—if it’s wrong for apes to discriminate against humans, it’s wrong for whites to discriminate against blacks—often goes unacknowledged.

Sci-fi and fantasy, more than any other genre, reflect the culture in which they originate. That’s why they seldom translate across time. Anyone who remembers the 1968 Planet of the Apes must recognize the cultural issues it brings to the surface. Though its anti-war message has become axiomatic, the racial concerns—if it’s wrong for apes to discriminate against humans, it’s wrong for whites to discriminate against blacks—often goes unacknowledged.Unfortunately, anyone who remembers the 1968 original understands why the 2001 remake fails so abjectly. Unlike the original, which lets us face realities we can’t discuss openly, the remake addresses scientific issues by hitting us in the face. It reduces racial concerns to Rodney King aphorisms (hey, did they give King’s line to an orangutan?!). Essentially, it replaces myth with spectacle. And audiences left theatres merely shrugging.

At root, these stories stagger because they never become culture-wide mythologies. The term mythology comes from the Greek mythos: the oral narratives that linked Greek society. But these narratives formed a larger single account. From Hesiod to Homer to Sophocles to Apollonius, these storytellers shared their gods and heroes. No one but George Lucas or his authorized agents can ever contribute to the Star Wars mythology.

At root, these stories stagger because they never become culture-wide mythologies. The term mythology comes from the Greek mythos: the oral narratives that linked Greek society. But these narratives formed a larger single account. From Hesiod to Homer to Sophocles to Apollonius, these storytellers shared their gods and heroes. No one but George Lucas or his authorized agents can ever contribute to the Star Wars mythology.Myth becomes proprietary. We cannot exchange narratives or grow together. No one really believes we’re trapped in the Matrix; no one expects to unearth a Stargate; and, while occasional fanatics adopt the Jedi religion, few sane people expect to use the Force to any effect. In this environment of ad hoc myth, we can never unify society behind our mythology. Society becomes fractionated, and Doctor Who fans feel self-superior in calling Battlestar Galactica groupies “nerds.”

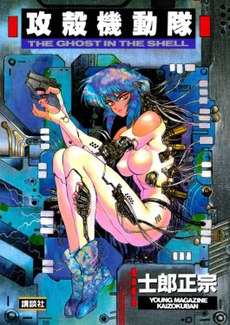

Occasional mythic concepts transcend their story and become universal. Cyborgs, for instance, occur in different settings, adapted to individual needs. Ghost in the Shell is distinct from the Borg but both touch common human fears—and hopes. Both examine, with optimism and dread, humanity’s potential merger with technology, dawning in modern medicine. The cyborg becomes a cultural myth that, like God, grows so vague that we lack a common image or definition.

Occasional mythic concepts transcend their story and become universal. Cyborgs, for instance, occur in different settings, adapted to individual needs. Ghost in the Shell is distinct from the Borg but both touch common human fears—and hopes. Both examine, with optimism and dread, humanity’s potential merger with technology, dawning in modern medicine. The cyborg becomes a cultural myth that, like God, grows so vague that we lack a common image or definition.So mythologies spring up for a moment, address a purpose, and become complete in themselves (like Star Trek) or disappear (like Dark City). Sure, the Internet nurtures fanfic communities, and occasional mythologies gain traction in their own right. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos has life beyond its author. But modern myths largely exist only as they are, with little room to appropriate or expand upon them.

Thus we continue to generate new myths. Whitt and Perlich suggest that ours is history’s most mythically rich society. Yet when we cannot make these myths our own, can they really answer our questions about ourselves? Doubtful. And without narratives to explain ourselves to ourselves, we risk becoming, in psychic terms, the poorest society in history.

Thus we continue to generate new myths. Whitt and Perlich suggest that ours is history’s most mythically rich society. Yet when we cannot make these myths our own, can they really answer our questions about ourselves? Doubtful. And without narratives to explain ourselves to ourselves, we risk becoming, in psychic terms, the poorest society in history.

No comments:

Post a Comment